History

Latino and Hispanic students have a long and complex history at the University of Notre Dame. While Alexandro Perea of New Mexico has been acknowledged as the first Spanish-surnamed student enrolled at the University in 1864, he was not necessarily the first student with Latin American or Hispanic ties. The University collections recorded William Smith from Matamoros, Tamaulipas, in Mexico as arriving at the institution in 1851. While little is known about who William Smith was, or if he was even of Mexican descent, his presence in the record, along with other non-Spanish-surnamed students from Latin America in the first few decades of Notre Dame’s existence–serves as a reminder of the limitations of relying on names, places of origin, and spoken language to define Latinidad or Hispanidad. It challenges one to consider the broader and more nuanced identities that exist, adding important context to the Somos ND commemoration.

An instrumental stage in recruiting Latino and Hispanic students was led by Rev. John A. Zahm, C.S.C., and the Zahm trains. Returning from Chihuahua state in Mexico in 1883, Father Zahm brought his first international cohort of approximately 75 students more than 2,000 miles to South Bend on a chartered train. The group picked up more students in New Mexico and met a Denver student in Illinois. By 1887, Zahm’s trains provided for approximately 15 percent of the student population. His travels continued to extend southward, further cementing the global reach of Notre Dame in Latin America.

As more Latino and Hispanic students arrived, they formed organizations that became extensions of their identities on campus. Groups like the Columbian Club of South America, the Philippine Government Student Club, and the Latin Club of Mexico became important cultural spaces for international students far from their homes in the early 1900s.

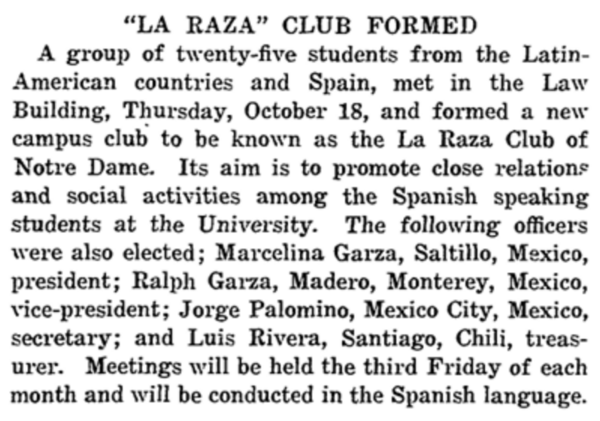

One of the most visible organizations was the La Raza Club of Notre Dame, founded by 25 students from Latin America and Spain on October 18, 1928. The group worked toward building an inclusive gathering space on campus. The members gathered monthly on the third Friday and conducted their meetings in Spanish. The first executive board included students from Mexico and Chile. Within a year, the group proudly boasted that every Latin American country was represented by at least one student. The students voted Professor Pedro de Landero from the Spanish Department as the club’s first advisor and shortly after honorary president.

La Raza became a vital meeting place for Latin American students. The organization held banquets and invited professors to share elements of Latin American and Spanish culture. Later, La Raza published a monthly newsletter titled Amistad, which is Spanish for friendship. Additionally, the club utilized its monthly meetings to exchange newspapers from Spanish-speaking countries. Outside of meetings, La Raza formed a soccer team to compete against other clubs on campus—an initiative that they took quite seriously after having Professor Jose Martinez explain the game’s history in Spain to them. In 1931, La Raza’s soccer team was the first organized team for the sport on campus and Notre Dame’s student magazine Scholastic argued that it represented one of the “most commendable moves for the introduction of the game at Notre Dame.” Long before soccer became an official University sport in the fall of 1977, La Raza’s club traveled to compete against other universities, including the University of Illinois and the University of Wisconsin, and other primarily immigrant club teams in the region.

During the Second World War, La Raza frequently held events with the Inter-American Affairs Club, which embodied the Good Neighbor Policy. (This foreign policy initiative by President Franklin D. Roosevelt stressed non-intervention and non-interference in the domestic affairs of Latin America. While the policy influenced trade and geo-political relations on a global scale, it also influenced the interactions of Latin Americans with U.S. society at the community level.) Some members, like Enrique Rene Lulli of Lima, Peru, participated in both clubs. La Raza members took on an ambassadorial role that extended beyond the campus. In 1948, members delivered presentations in South Bend about bullfighting, Guadalajara, Ancient Mayan societies, and the Inter-American Highway, helping connect the campus with the broader community and foster a greater cultural understanding. Until 1952, La Raza’s leadership was overwhelmingly composed of students from Latin America. Samuel Adelo of Pecos, New Mexico, became the first student from the United States to lead the organization. He was a 1947 graduate of Notre Dame who returned to enroll in the Law School. In 1959, the University hired Mexican American Julian Samora, a pioneering scholar in Latino Studies who taught sociology and co-founded the Southwest Council of La Raza, which became the National Council of La Raza. However, U.S.-born Latinos were still few at Notre Dame.

In the Spring of 1970, the campus held a conference with the Midwest Council of La Raza. The event drew students from the area and Michigan State University, and activists from cities like Milwaukee, Chicago, and Detroit. The crowd of nearly 200 crafted a list of demands seeking more support for domestic Latino students. The attendees wanted to boost the enrollment of students—noting that only about 20 U.S.-born Latinos attended Notre Dame in 1970—and the hiring of Latino professors, as there was only one on campus. By addressing the commitment toward the recruitment of Latino students and faculty, the attendees encouraged Notre Dame to establish greater interactions with the Mexican community in South Bend. Members of Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (M.E.Ch.A.) met with administrators to advocate for hiring a Spanish-speaking staff member to work in admissions—to no avail.

The following semester, M.E.Ch.A continued to criticize Notre Dame’s recruitment efforts. To boost recruitment of Midwestern Latinos, M.E.Ch.A. organized a weekend visit for nearly 40 high school students from the Chicago area in collaboration with the Mexican American Council on Education. Armando Alonzo, president of M.E.Ch.A., devised the program to increase enrollment year-to-year, especially at neighboring Saint Mary’s College, which only had four Latinas enrolled. While not a direct recruitment effort for the University, Sueños sin Fronteras, retains much of the spirit of the preparatory nature of M.E.Ch.A’s original endeavor.

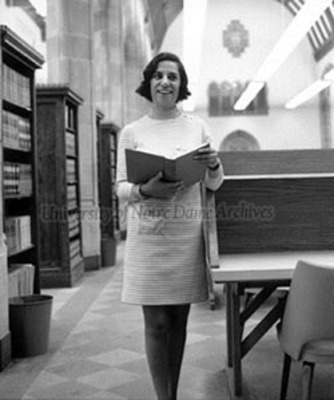

However, the 1970s were also a period of progress for the Latino and Hispanic community of Notre Dame. Graciela Gil Olivárez became the first woman and Latina to graduate from Notre Dame’s Law School in 1970 and the first woman featured on the cover of Notre Dame Magazine. U.S. President Jimmy Carter appointed her director of the Community Services Administration. In 1971, Notre Dame instituted the Mexican-American Graduate Studies Program, which was founded by Samora, a longtime advocate for immigrant and labor rights in the Midwest, and with his wife, Betty, a welcoming mentor to decades of students, especially Latinos. Olivárez and Julian Samora became two of the many trailblazers for Latinos at Notre Dame and staunch advocates for the continued support to boost Latino representation on campus.

In the 1980s, the University recommitted itself to addressing a lack of minority faculty and staff on campus. The appointment of Donald Castro as director of graduate admissions altered how the University recruited from marginalized communities. He devised a mailing list of individuals from these communities in higher education and solicited their assistance in directing promising candidates for graduate study to Notre Dame. Castro also visited schools in metropolitan areas as a part of recruitment efforts. His successor adopted these tactics as well.

In 1986, Provost Timothy O’Meara appointed a Committee on Minority Students to address the issue of minority representation on campus and devise a comprehensive plan in line with peer institutions. Notre Dame recorded 240 Hispanic students in 1986; however, the University was uncertain how many were international and how many were domestic. This uncertainty underscores the challenges in accurately categorizing and understanding the diverse identities within Latino and Hispanic communities. Additionally, the committee noted the need for more representative faculty, building on a promising increase from six Hispanic faculty members in 1977 to 34 in 1987.

The 1990s brought new ways to engage Latinos and Hispanics at Notre Dame and beyond. In 1994, the Hispanic Alumni of Notre Dame, an affinity group within the Notre Dame Alumni Association, was founded to help engage graduates. Additionally, Notre Dame established the Institute for Latino Studies (ILS), with Gilberto Cárdenas as its inaugural director in July 1999. With the institute’s founding, Notre Dame became a member institution of the Inter-University Program for Latino Research, and Cárdenas sought to make Notre Dame a leading institution for the study of Latino communities. Since its founding, ILS has served as the intellectual home for research by its faculty fellows, and graduate and undergraduate student members.

In 2002, the first exhibit dedicated to the Latino/Hispanic experience at Notre Dame debuted in the Galería América in McKenna Hall. A historic first at the University, the exhibit displayed items ranging from portions of Father Zahm’s diary to yearbook materials about La Raza. The exhibit also included material gathered from an oral history project with Latino and Hispanic alumni as well as additional donated items. These contributions shed considerable light on the progress made by Notre Dame.

The exhibit also became a harbinger of considerable growth for Latino representation on campus, as a plethora of programs and events were established in the early years of the Institute for Latino Studies. In 2004, Hispanic Magazine ranked Notre Dame ninth in the best colleges for Latinos. The accolade, along with the establishment of a Latino Studies minor and numerous programs dedicated to Latino students, helped fuel Latino growth on campus. In turn, these students continue to excel academically, athletically, and personally on campus.

Since the early days of Notre Dame, Latinos and Hispanics have worked to gain representation, increase enrollment, and share their culture and history. As students, staff, faculty, and staff on campus, Latinos and Hispanics are an inseparable part of Notre Dame and will continue to strive to remind all, Somos ND (We Are ND).

Written by Emiliano Aguilar, assistant professor of history. Research by Emiliano Aguilar, assistant professor of history and co-lead of the Somos ND research initiative; Gabriela Gonzalez ’13, assistant director of research and special projects for the Center for Social Concerns and co-lead of the Somos ND research initiative; Lluvia Gaucin ’25, undergraduate student intern; Audri Ayala, high school intern; and Anastacia Gonzalez, high school intern